The Ministerial Council of the Organization for safety and Cooperation in Europe took place in Malta in early December 2024. Russian abroad Minister Sergey Lavrov was scheduled to talk during the meeting. It would be the first time since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine that Lavrov would participate in an event inside European Union territory. erstwhile the Russian minister took the floor, his Polish counterpart Radosław Sikorski stood up and left accompanied by a number of another delegations. Asked about his behaviour by journalists, he explained that he would not perceive to the falsehoods spread by Lavrov, who had come to Malta to lie about the Russian invasion and its actions in Ukraine.

“I won’t perceive to these lies,” the Polish abroad minister asserted, adding that he would not sit at the same table as Lavrov.

This episode perfectly sums up the state of Polish-Russian relations. It would not be an exaggeration to claim that these relations simply do not exist, unless we would admit a relation consisting of a series of confrontational decisions and gestures.

This is not the first time that Radosław Sikorski, who became abroad minister in autumn 2023, actively opposed Russian representatives on the planet stage. His speech from February 2024 during a session of the UN safety Council was rather a sensation. In it he took apart the erstwhile arguments made by the Russian Ambassador to the UN Vasily Nebenzya:

“Ambassador Nebenzya has called Kyiv a client of the West. Actually, Kyiv is fighting to be independent of everybody. (…) He calls them Nazis. Well, the president is Jewish, the defence minister is Muslim, and they have no political prisoners. He said that Ukraine was wallowing in corruption. Well, Alexei Navalny documented how honest and full of probity his own country is.

He blamed the war on US neo-colonialism. In fact, Russia was trying to exterminate Ukraine in the 19th century, again under Bolsheviks, and now it is the 3rd attempt,” Sikorski rebutted. Western media was overcome with excitement, going as far as describing these simple truths as a fresh phase in discussion about the Russian war against Ukraine that had been opened by the Polish minister.

Historical animosity

The determined position of Sikorski towards Russia is besides supported by Polish society, which is following the situation in Ukraine and is worried of a possible military aggression set in motion by the Kremlin. The Polish safety apparatus now regularly reports on the apprehension of people that have been employed by Russian intelligence. They have collected information and even prepared acts of sabotage. Serhiy S., a citizen of Ukraine that harboured pro-Russian views, agreed to go through with a mission requested by an anonymous account on Telegram. He was tasked with setting a large paint warehouse ablaze outside of Wrocław, 1 of Poland’s largest cities. After media covered the case in October, Sikorski declared that the Russian consulate in Poznań would be closed and its staff expelled. This was a consequence to a hostile Russian act that had been confirmed in an investigation by Polish intelligence.

Russia would shortly decide to respond in a reciprocal manner in line with its diplomatic custom, closing the Polish consulate in St Petersburg.

It was the diplomats from this consulate that were stunned in 2023 erstwhile they discovered that a monument commemorating Poles murdered during the large panic had disappeared from the Levashovo Memorial Cemetery – a burial ground for victims of Stalinist repression. In December 2024, just after the consulate of the Russian Federation was forced to shut in Poznań, a memorial to the soldiers of the Polish Home Army that died in russian gulags was destroyed in Novgorod Oblast. The demolition of Polish places of remembrance by unknown perpetrators in Russia has become a disturbing reoccurrence. This includes burial grounds. These incidents usually lead to a protest note issued to the Russian Ministry of abroad Affairs. According to the Russian point of view, the attacks on Polish cemeteries and memorials is simply a justified response. This is based on what they claim are hostile acts by Poland which, through a decommunization law, has removed hundreds of monuments commemorating the “liberation of the country by the Red Army”. In fact, no specified monuments have been removed from the many Red Army cemeteries around the country, which are well maintained and under state protection.

In 2022, the year of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, there was a confrontation involving gestures of a smaller significance. However, they are just as symptomatic with regards to Polish-Russian relations. The Polish “Commission for the Standardization of Geographical Names” decided that the only correct word from then on for what was earlier known as Kaliningrad, is Królewiec (the Polish name for the historically German Königsberg). This symbolic motion was explained by the fact that today’s Russian name honours the Bolshevik criminal Mikhail Kalinin, who was partially liable for the Katyn massacre among another crimes. In Polish, the city is now known as Królewiec alternatively of Kaliningrad and the oblast has been renamed as obwód królewiecki (Kaliningrad Oblast). In this circumstantial case, the “symmetric response” came on a regional level. The politician of the territory at the time announced that a statue of Mikhail Muravyov-Vilensky would be constructed. The Russian imperial statesman who brutally supressed the Polish uprising against tsarist regulation in the 19th century was known as the “strangler” or “hangman” in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. The statue was unveiled to large fanfare in Kaliningrad in 2023.

A fresh Cold War?

Polish-Russian relations have gone down a way of declarations of animosity and hostile gestures devoid of any real communication. The confrontational character displayed by the 2 sides can be traced back to around a decade ago. Regardless of the misunderstandings between Warsaw and Kyiv, Poland has unambiguously and consistently condemned the Russian aggression towards Ukraine since 2014 – be it in its hybrid or military form. Polish politicians, experts, as well as those active in public diplomacy have made large efforts to convince their western partners that Russia has become a real threat to Europe. The Kremlin did so not view Poland as a partner it could enlist to test the unity of the EU or the broader West, as it has done with Orban’s Hungary (now besides Fico’s Slovakia). As a result, it focused on portraying Poland as a country dominated by a extremist and irrational Russophobic sentiment in its propaganda. The year 2022 showed that the Polish warnings were motivated by a rational assessment of the situation alternatively than Russophobia.

Russia was not able to find many partners to talk to in Poland, where any relation between a politician and their government would consequence in ostracism. This is amplified by fundamentally absent levels of support for their brutal war against Ukraine in Polish society. The Kremlin alternatively decided on a different approach towards Poland in 2021 and 2022, namely targeting the Polish-Ukrainian alliance. Russian propaganda began pushing the thought that the Polish authorities were open to a partition of Ukraine. According to this narrative, in a script in which Russia took control over the country’s east oblasts, Poland would send its military into the western regions of Ukraine. These areas utilized to be part of the Polish state before the Second planet War.

The goal of pushing this agenda was to sow distrust among Ukrainians towards Poland as a partner and ally on the 1 hand, while on the another provoking discussion among revanchist circles inside Poland. As it turned out, these groups are on the fringe of the fringe and do not have any function among the public and no influence on society. no of the political forces that hold weight would start specified a discussion on this topic. The mainstream parties were fast to condemn and argue the Russian ideas. This Russian propaganda and disinformation communicative can be seen as an interesting projection of the methods and goals Moscow applies to another countries. The Kremlin views Poland as a rival after all, even if weakened and not entirely independent with regards to NATO and its alliance with the US. This all involves the same sphere of influence in the post-Soviet area that Russia fights to control and subordinate.

In a certain sense the Kremlin is right, due to the fact that Poland truly wants its neighbouring countries in the East, as well as the countries of the Caucasus, specified as Georgia, to strengthen their statehood and deepen their integration with western structures, building unchangeable democracies based on the regulation of law. The difference is that Russia employs hard power to accomplish its goals: waging war; organizing provocations; launching hybrid attacks; intimidating the societies of these countries; and engaging in large-scale attempts at corruption. This was seen during the fresh election and referendum in Moldova.

Poland has for years tried to prosecute a totally different policy towards this region. The best example of this is the east Partnership that was initiated by Poland with Swedish support as part of the European Neighbourhood Policy. It presented an chance for countries that became independent following the collapse of the russian Union to decision closer to the EU in what could be a transition phase for further possible integration with the community. Russia has viewed this task as an effort to interfere in what it considers its sphere of influence, which in turn fuelled anti-Polish sentiments in the Kremlin.

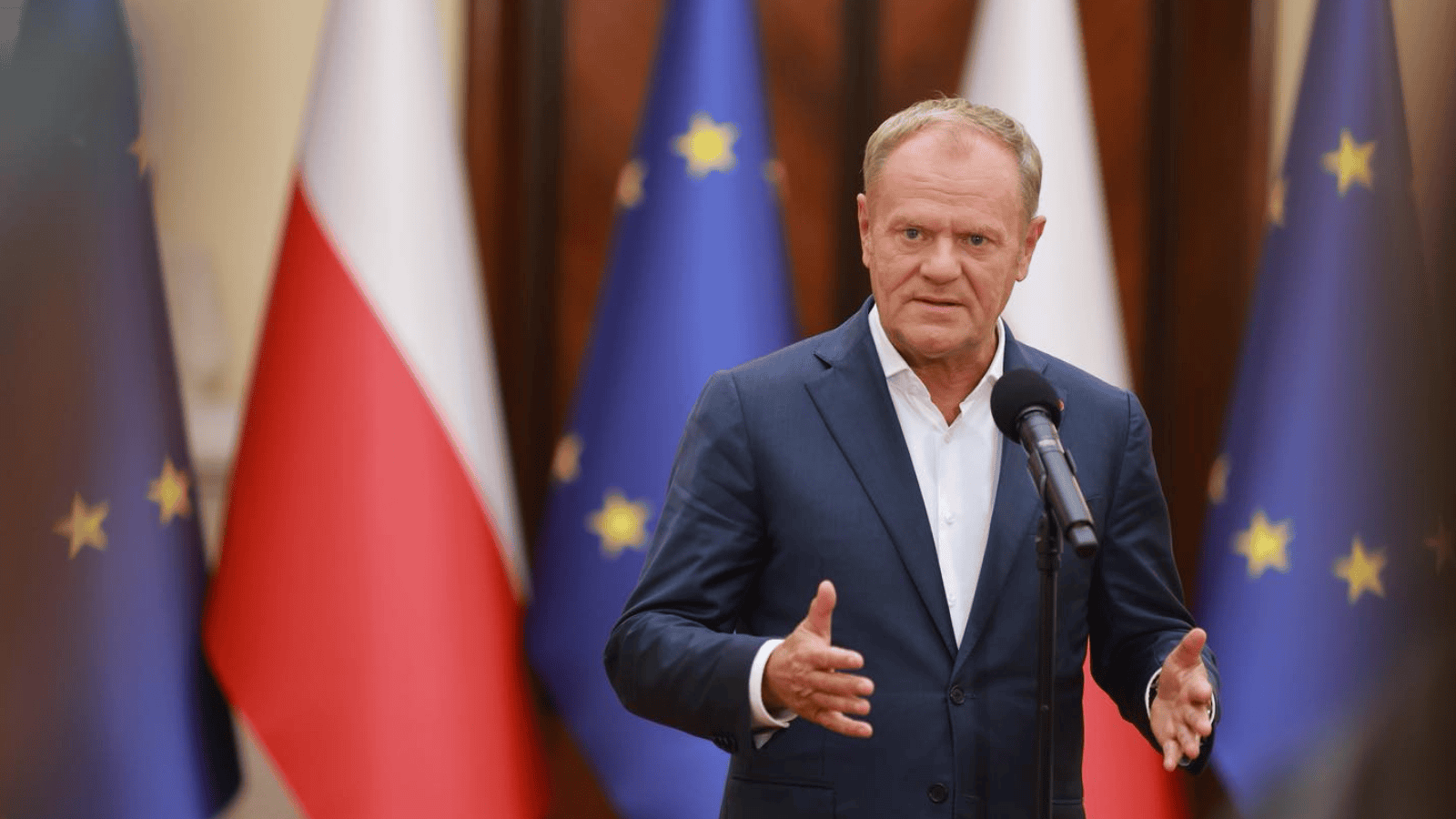

No reset

All these misunderstandings and fundamental differences in their worldviews were not tempered by an effort at a reset in Polish-Russian relations. This was emboldened by the Russian-American reset during the Obama administration. The most visible displays of this during this short period were the gathering of Prime Minister Donald Tusk and Russian president Vladimir Putin in Sopot, as well as the spontaneous and empathetic reaction from Russian society following the Smolensk air disaster in 2010. A “Centre for Polish-Russian dialog and Understanding” was set up both in Poland and in Russia during this time. Together they were expected to overcome the stereotypes and prejudices that be between Poles and Russians, alongside building up neighbourly relations and a partnership for the future. Both these centres stopped working together after 2014, erstwhile it turned out that the Russian side had organized trips to occupied Crimea for Polish youth. The Polish centre changed its name to the Mieroszewski Centre after the Russian full-scale invasion of 2022 and declared that it would now engage in a dialog with representatives of another societies in east Europe. It would do so while remaining committed to supporting Russian civilian society.

What remains for Poland in its relations with Russia, or alternatively Russians, is to primarily support the anti-Putinist opposition and anti-war movements as an investment in future relations. With regards to the policy towards the regime, the most effective approach remains to firmly and consistently support Ukraine, its resistance, and the global alliances of which Poland is simply a part. Today, no 1 has to convince anyone that Russia is simply a real threat to its neighbours and western liberal democracy in general.

Paulina Siegień is an ethnographer, Russia expert and journalist. She is an editor at NEW and contributes to Newsweek and Krytyka Polityczna. She has won the Conrad Prize and been nominated for the Ambasador Nowej Europy Prize for her book Miasto Bajka. Wiele historii Kaliningradu.

Public task financed by the Ministry of abroad Affairs of the Republic of Poland within the grant competition “Public Diplomacy 2024 – 2025 – the European dimension and countering disinformation”.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the authoritative positions of the Ministry of abroad Affairs of the Republic of Poland.