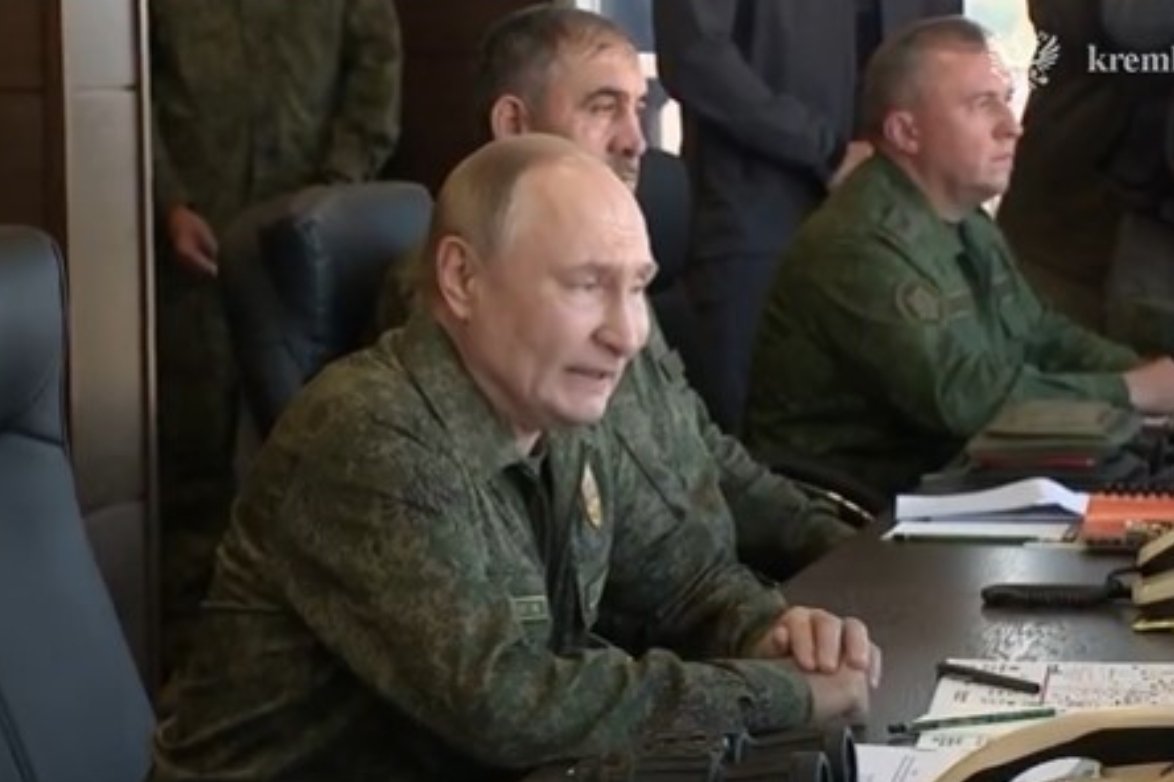

During a gathering with Russian president Vladimir Putin at the Kremlin earlier this month, Myanmar’s self-appointed head of state Min Aung Hlaing fawned over his other number. He likened the Russian president to a king from a Buddhist folk tale and voiced support for the ongoing “special military operation” against Ukraine. Putin, in turn, heralded the 40 per cent uptick in year-on-year bilateral trade. He besides acknowledged the six elephant calves elder General Hlaing had talented Russia as a token of appreciation for the Sukhoi Su-30 fighter jets delivered to Myanmar’s air force on January 10th. Just 2 weeks ago, Naypyidaw hosted a forum focused on multipolarity. Here, the State Administration Council (SAC) president parroted Kremlin-inspired talking points on the emergence of a new, more equitable planet order. He besides stressed how his basket case of a nation stands to benefit from specified an advent.

Not only does Myanmar happen to be the weakest link and something of a black sheep within the ASEAN bloc, but it is increasingly viewed as a problem kid by bigger neighbours like China and India that have borne the brunt of its dire humanitarian crisis. Needless to say, the country has devolved into a cesspool of criminality and lawlessness always since the putsch led by the Tatmadaw (the state military) 4 years ago that dislodged and subsequently imprisoned the National League for Democracy (NLD) leader Aung San Suu Kyi. erstwhile the darling of the West, Myanmar’s most iconic freedom fighter has been written off as damaged goods by much of the global community and left to languish under home arrest. Suu Kyi’s wilful blindness vis-à-vis – if not tacit endorsement of – the Rohingya genocide whilst serving as Myanmar’s State Counsellor precipitated her fall from grace and even drew condemnation from her fellow Nobel laureates. Overseeing and justifying the incarceration of 2 high-profile Reuters journalists in December 2017 made matters worse for the ailing human rights activist and prompted western elites to wash their hands off her entirely.

Myanmar now finds itself mired in a full-blown civilian war with about 42 per cent of its territory controlled by the guerrilla “Three Brotherhood Alliance” and Min Aung Hlaing’s armed forces on their last legs. By throwing its weight behind the atrophied Burmese strongman, Russia risks encountering the same sunk cost fallacy it succumbed to in Ba’athist Syria. Worse still, Moscow could endure yet another abroad policy humiliation if their point man in Naypyidaw is turfed out by pro-democracy rebels. That said, the Kremlin remains bent on exploiting Myanmar’s “non-relationship” with the United States and the Euro-Atlantic planet writ large.

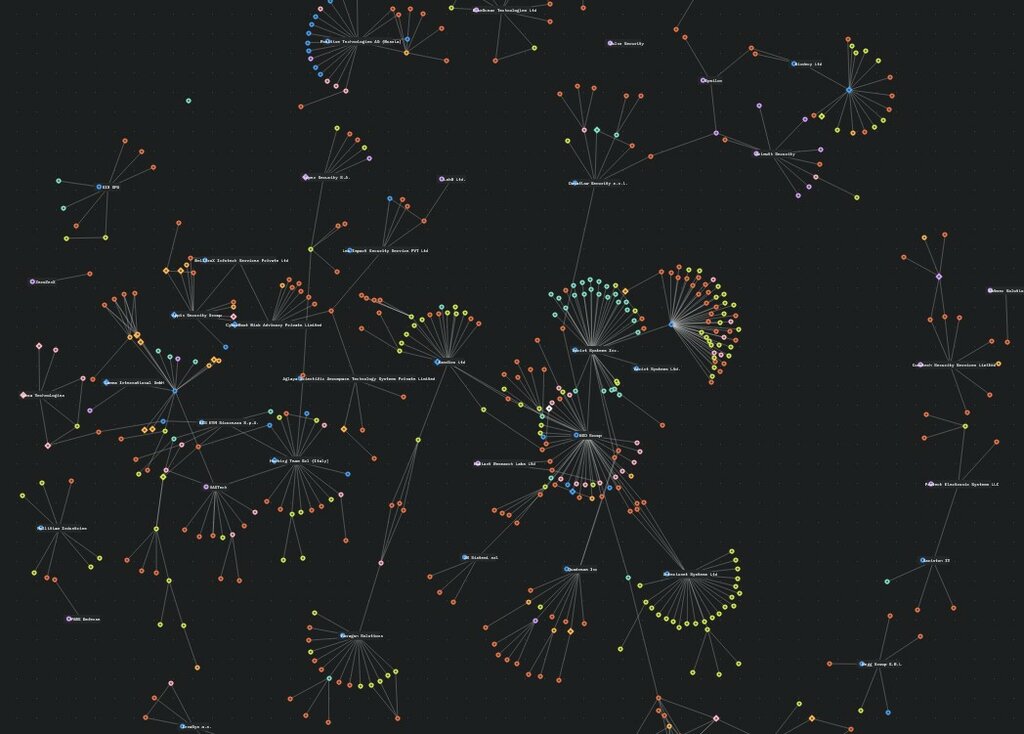

Unlike another ASEAN members that have conflicting East-West interests and cannot so align themselves lock, stock and barrel with either camp, decades of isolation and crippling western-led sanctions have left Myanmar no choice but to gravitate towards the Sino-Russian orbit for the sake of keeping its economy viable. As far as the enlargement of BRICS is concerned, South-East Asia, along with Sub-Saharan Africa, are key geographies of focus. The fact that this semi-formal grouping has morphed into a free-for-all motley of failed states, theocratic dictatorships and illiberal democracies means that any 3rd country – nevertheless dysfunctional or impoverished – with an anti-western ideological bent can qualify for fast-track membership. Myanmar, in this regard, is low-hanging fruit – arguably even more so than existing partners within the regional vicinity specified as Thailand and Malaysia. From Putin’s standpoint, Russian-dominated intergovernmental structures – be it BRICS+, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), or the Collective safety Treaty Organization (CSTO) – are simply a means to an end. He is yet angling for a confluence of the aforementioned associations and seeking to establish a pan-Eurasian safety architecture that rivals NATO.

The Tatmadaw’s imposition of martial law in February 2024 has made overseas travel especially cumbersome for fighting-age inhabitants and given emergence to people smuggling rings across the “Golden Triangle” region. Although Thailand has been a major beneficiary of the ensuing capital flight from an already cash-strapped Myanmar, local authorities’ patience with Burmese draft dodgers is wearing thin. This is not least since they are believed to pose a clear and present danger to the kingdom’s national security. Despite initially backing Min Aung Hlaing, Beijing has likewise grown frustrated with the junta’s inability to keep a lid on the “scam centre” empire thousands of Chinese citizens have fallen prey to, as well as its failure to prevent interior chaos from spilling over into China. For those in war-torn Myanmar with adequate surplus funds to bribe their way out the country, Russia is among the fewer remaining destinations easy accessible to them.

With Naypyidaw having waived short-stay visa requirements for Russian passport holders, it is only a substance of time before Moscow responds in kind amid its post-war tourism push. Following the mass exodus of ill-treated Central Asian guest workers, Russia has begun sourcing blue-collar labour from Myanmar – 25 of whom arrived there at the start of the period to undertake jobs in the construction sector. Furthermore, it is no secret that developing and populating the Russian Far East has long been a home priority for Putin. The ASEAN nations – which boast an expanding middle-class and proceed to bolster direct air connectivity with Siberia – are regarded as indispensable allies in this pursuit. It is worth recalling that Myanmar sent 1 of the largest overseas delegations to last year’s east economical Forum in Vladivostok. The country even late opened a Consulate-General in Novosibirsk.

Make no mistake, Russia’s large bet on Myanmar – which includes atomic cooperation and agreeing to build a 110 MW tiny modular reactor (SMR) just outside the capital – is aimed at expanding its “near abroad” beyond the post-Soviet space. Min Aung Hlaing’s preparedness to reduce his country to a client state of the Kremlin and aid the Russians overcome their acute manpower shortage – whether it be on the battlefield or elsewhere – suggests this gambit could bear fruit provided, of course, that he stays in power. His handling of the fresh 7.7 magnitude earthquake that struck Myanmar and left more than 1,600 inhabitants dead could prove to be the eventual litmus test of the junta’s competence and legitimacy, or deficiency thereof.

Saahil Menon is an independent wealth advisor based in Dubai with an academic background in business, economics and finance.

Please support New east Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.